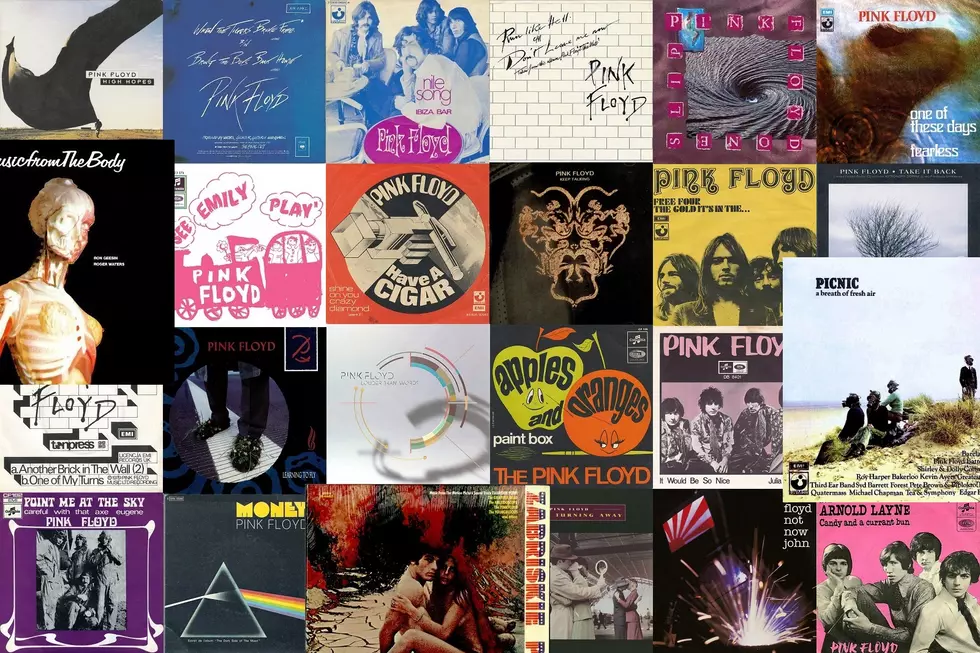

All 167 Pink Floyd Songs Ranked Worst to Best

To explore Pink Floyd’s entire career of recordings is to take a trip through time and space. Their songs uncover a beautiful but troubled world, while also plunging us deep into the mysteries of the human mind.

From 1967 until 2014 – when the band released their last album, six years after founding member Richard Wright’s death – Pink Floyd created some of rock’s most fiercely creative, yet remarkably accessible music. They crafted heady, experimental concept albums that pondered humanity’s greatest questions but were also capable of delivering a sharp pop single – whether psychedelic or disco-tinged. In spite of having only five full-time members through the duration of the group’s run, Pink Floyd evolved through multiple eras that could alternate between extensive collaboration and strong-willed leadership.

This list of all 167 Pink Floyd Songs Ranked Worst to Best runs the gamut, including every studio-recorded track from 15 albums, a handful of non-LP singles and b-sides, some soundtrack and compilation appearances and a few overlooked pieces that came out decades after they were first put to tape.

Due to Pink Floyd’s penchant for multi-part conceptual works, a “song” isn’t as well-defined as it might be with other bands. So, for the most part, we delineated songs as tracks: If Pink Floyd cut them into little pieces, then we assessed them individually, even if they are songs that are usually played together on radio (i.e. “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse”).

There were some exceptions to this rule – notably The Endless River, which was conceived as four suites. Each “side” of that release became its own song. We gave the same treatment to the multi-part suites on the studio half of Ummagumma, while leaving behind the concert-recorded disc entirely. We avoided the demos on the “Immersion” box sets of The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here and The Wall, because those pieces turned into full-fledged tracks later on. We did include some previously unreleased material that eventually saw the light of day, but only if it was officially released before Pink Floyd’s last album in 2014.

With that said, let’s set the controls for the heart of Pink Floyd.

167. “The Grand Vizier's Garden Party (Parts 1-3),” Ummagumma (1969)

The experimental, studio-recorded half of Ummagumma was probably more fun to make than it is to listen to. That simply must be the case with Nick Mason’s directionless contribution – a seven-minute jumble of percussive noises flanked by flute solos played by the drummer’s then-wife Lindy.

166. “A New Machine (Part 1),” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

It’s tough to decide what is more annoying about “A New Machine.” Is it David Gilmour’s naked attempt to connect the new-recipe Floyd to the band’s classic material (vocoder, robotic vocals, short bookend tracks to a larger piece, the obvious reference to “Welcome to the Machine”)? Or is it just the grating, melody-deprived sound of Pink Floyd’s new leader howling for high concepts in empty lyrics?

165. “A New Machine (Part 2),” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

Ditto, except that Part 2 is less than half the length of Part 1, which makes it less irritating. Exactly one spot less irritating.

164. “Two Suns in the Sunset,” The Final Cut (1983)

Roger Waters’s tenure in Pink Floyd (give or take a Live 8 appearance) culminates in a nuclear holocaust. It’s a strangely stone-faced protest song spiked with scare tactics – including a line about never again hearing your loved ones’ voices followed by a girl screaming “Daddy, Daddy!” You know, just in case lyrics such “As the windshield melts and my tears evaporate, leaving only charcoal to defend” were too subtle. And, even worse than an atomic fireball, Waters tacks on a cheesy sax solo to deliver us to the apocalypse.

163. “Terminal Frost,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

Speaking of atrocious saxophones, this Momentary Lapse of Reason instrumental includes a lifetime’s supply of new-agey squealing. It sounds like Kenny G’s attempt to make a proggy soundtrack for the the channel on your hotel TV that tells you how late the lobby bar stays open.

162. “Don’t Leave Me Now,” The Wall (1979)

No album spans the best, middling and worst Pink Floyd tracks like The Wall. There are less consequential songs from this double LP, but none more unpleasant than this plodding exercise in dissonance and misogyny. In character as the depressive, delusional and violent rock star named Pink, Waters whines “Why are you running away?” (for the second time in two tracks; it’s also the final line of “One of My Turns”). As Pink, Waters longs to resume his abusive ways, but the real torture is listening to his screechy, alley-cat yelp.

161. “Heart Beat, Pig Meat,” Zabriskie Point soundtrack (1970)

Pink Floyd were in the throes of their most experimental phase when film director Michelangelo Antonioni tapped the band to record music for 1970’s Zabriskie Point. Their least interesting contribution was this mess of steady drums, a wandering keyboard and sound clips seemingly captured from a nearby television. But the intertwining effects and music would prove to be good practice for later masterpieces.

160. “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast,” Atom Heart Mother (1970)

This 13-minute slab of musique concrete fulfills a request that (probably) no Floyd fan ever made: “What does roadie Alan Styles like for breakfast, can we hear him making it and could the guys in the band noodle around (in a very non-psychedelic manner) as he fries bacon, muses about marmalade and pours a bowl of Rice Krispies?” Now, who’s hungry?

159. “The Post War Dream,” The Final Cut (1983)

With a dearth of melodic ideas, Waters pilfers the chord progression to “Sam Stone” by John Prine. Even more troubling is Waters’ casual use of a derogatory term for the Japanese. Some have suggested this is a reference to circa-’45 attitudes or an interpretation of a blue collar perspective, but Waters is not singing in character here: He mentions his late father in the song’s second line.

158. “A Spanish Piece,” More (1969)

This harmless but forgettable goof is less notable for Gilmour’s flamenco work or his poor approximation of a Spanish stereotype than for being the guitarist’s first solo songwriting credit in Pink Floyd. He got better.

157. “Seamus,” Meddle (1971)

Another goof, this song features Steve Marriott’s titular dog howling along with Gilmour, Waters and Wright as they play a rudimentary blues. Among fans, “Seamus” is a perennial candidate for the stupidest track in the Pink Floyd catalog. It’s certainly the worst song on an otherwise great album.

156. “Stop,” The Wall (1979)

Broadway-style connective tissue to bridge “Waiting for the Worms” and “The Trial,” and nothing more.

155. “Party Sequence,” More (1969)

For a few ticks more than a minute, Mason pounds out an ersatz tribal rhythm on the bongos while his wife Lindy toots on a penny whistle. Neither a compelling addition to the soundtrack to Barbet Schroeder’s film, nor is it offensive.

154. “Yet Another Movie,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

With A Momentary Lapse of Reason, listeners’ mileage may vary in relation to a tolerance of the trappings of ’80s rock production. But “Yet Another Movie” is worse than just gauzy synths and airless percussion. It’s a rather dull takedown of formulaic movies, spelled out in Hollywood cliches and soundbites from Casablanca – for reasons that remain unclear. Gilmour can cut through the confusion (and compression) with a solid solo, though.

153. “Round and Around,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

This circular coda to “Yet Another Movie” was split from its parent track on 1988 live album Delicate Sound of Thunder as well as later reissues of A Momentary Lapse of Reason. There’s no great reason for this. It’s a minor instrumental that features the kind of electric licks Gilmour can toss off in his sleep.

152. “TBS9,” The Endless River (Deluxe Edition) (2014)

While Gilmour, Mason and Wright were making The Division Bell, engineer Andrew Jackson compiled some of their unused recordings into an instrumental album he called The Big Spliff. Pink Floyd decided not to roll out the stuff at the time, but allowed two segments to appear on expanded editions of the 2014 swan song, The Endless River. “TBS9,” one of those two segments, is a wafty wisp that lives up to its pedigree as a bonus track on an album of leftovers.

151. “The Hard Way,” The Dark Side of the Moon (Immersion Box Set) (2011)

Only two tracks from Household Objects, Pink Floyd’s aborted Dark Side follow-up, were ever completed. This stiff instrumental – created, as the LP’s title suggests, with household objects – is more interesting as an experiment than actual music.

150. “Goodbye Cruel World,” The Wall (1979)

As far as act breaks go, this one is short and simple, explaining Pink’s self-imposed isolation in terms even the most oblivious listener could understand. “Goodbye” lumbers inevitably towards half-time – although the abrupt cut on the final word is effective.

149. “More Blues,” More (1969)

This start-and-stop blues tune is as banal as what the quartet presented on “Seamus.” But, hey, no howling dog.

148. “Get Your Filthy Hands Off My Desert,” The Final Cut (1983)

Waters leads off Side 2 of his anti-war screed with an chamber music nursery rhyme comparing world leaders to greedy children. The Pink Floyd singer/bassist’s sledgehammer commentary is slick and snarky, and the explosion sound effect is striking, but Peter Gabriel’s “Games Without Frontiers” makes Waters’ work seem like, ahem, child’s play.

147. “TBS14,” The Endless River (Deluxe Edition) (2014)

More substantial and interesting than the other slice of The Big Spliff to see official release, but only slightly. Halfway through, it seems to be headed in an actual direction, although that ends up being a return trip to the Weather Channel's “Local on the 8s.”

146. “Wine Glasses,” Wish You Were Here (Experience/Immersion Box Set) (2011)

The other finished track from the ill-fated Household Objects project contains some ethereal beauty via a “wine glass harp,” but the ambient hum would be put to better use as a component in the opening of “Shine on You Crazy Diamond.”

145. “Dramatic Theme,” More (1969)

Mood music with some bendy, echoing guitar from Gilmour.

144. “Several Species of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together in a Cave and Grooving with a Pict,” Ummagumma (1969)

Pink Floyd meets the Chipmunks. If you were grading songs merely by how many repeat listens you would grant them, Waters’ Ummagumma experiment with vocal effects and tape speeds might land at the very bottom. Yet there’s something impressive lurking amidst the rhythms he creates out of his nattering, pretend woodland creatures. Plus, the track’s “Scottish” farmer presages Waters’ embodiment of The Wall’s fearsome schoolmaster.

143. “One of the Few,” The Final Cut (1983)

That particular schoolmaster doesn’t just show up on The Wall; he earns a backstory on Floyd’s follow-up LP. This time, his abusive behavior towards his students isn’t blamed on his “fat and psychopathic” wife, but on being a World War II veteran. As with many of The Final Cut’s worst offenses, this short track is too simple and deprived of melody to resonate in any meaningful way. But the schoolmaster’s war-time tale gets fleshed out elsewhere.

142. “Love Scene (Version 6),” Zabriskie Point soundtrack re-release (1997)

Despite taking their name from a pair of bluesmen, Floyd’s straight blues compositions aren’t any more remarkable than what most bar bands could deliver in a seven-and-a-half-minute blues jam. On the other hand, none of those bands features a guitar played by David Gilmour, who is a delight even when derivative.

141. “Bring the Boys Back Home,” The Wall (1979)

More of The Wall’s connective tissue – or should we call it mortar? If so, it’s mortar of the most bombastic variety, complete with a few dozen drummers, an operatic choir and a soaring string section. Bold and impressive, but it’s still not much of a song.

140. “Vera,” The Wall (1979)

This eight-line poem, backed by a stark orchestra, is the quiet before the bluster of “Bring the Boys Back Home.” The track features a yearning Waters struggling with the optimism of Vera Lynn’s legendary wartime ballad, “We’ll Meet Again.” Like his character, Waters didn’t get to meet his father after World War II. He wrote better-realized songs about this emotional hole in his life, but the singer’s plaintive emotion comes through here.

139. “Quicksilver,” More (1969)

As slippery and difficult to corral as its title suggests, this avant-garde instrumental discovers a spooky sort of intrigue – mostly by way of Wright’s dream sequence organ playing. It maintains a mood, if little else.

138. “Sysyphus (Parts 1-4),” Ummagumma (1969)

It’s appropriate that keyboardist Wright named his Ummagumma suite after the Greek mythological character Sisyphus, because the instrumental piece opens with the pomp and circumstance of a soundtrack to a sword-and-sandals epic. It mutates, rather schizophrenically, from there into a clattering piano number (Part 2), a tangle of percussive noises (Part 3) and an ambient drone (Part 4) before somehow finding its way back to the opening theme in the 13th minute. It sounds like a piece written to impress a college music professor.

137. “Empty Spaces,” The Wall (1979)

As Pink wonders how to fill the spaces in his “wall,” Waters had to put “Empty Spaces” in the place of a longer piece titled “What Shall We Do Now?” because of vinyl running time issues. The song maintains the former’s eerie, slow-motion surge.

136. “The Dogs of War,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

Maybe the most egregious instance of David Gilmour trying to make ’80s Pink Floyd appear to be ’70s Pink Floyd, “The Dogs of War” attempts to conjure memories of Animals, but lacks that album’s musical dynamism and razor-sharp commentary. Gilmour – the only Floyd member on this song – turns in a nifty guitar solo (niftier in concert), but mostly overcompensates by snarling the words. It’s all growl and no bite.

135. “Up the Khyber,” More (1969)

Mason’s no Buddy Rich and Wright wouldn’t be confused for Thelonious Monk, but they can fake it for a couple of minutes on this jazzy interlude, continuing a project that has more interludes than substance.

134. “Love Scene (Version 4),” Zabriskie Point soundtrack re-release (1997)

Wright’s best contribution to the Zabriskie sessions (“The Violent Sequence”) was rejected for use in the film; Pink Floyd later refashioned it into “Us and Them.” This solo piano piece isn’t quite so hauntingly epic, though Wright discovers the darkness between the dappled sunlight of his pretty composition.

133. “The Fletcher Memorial Home,” The Final Cut (1983)

For a brief moment – the instrumental break between verses three and four – this sounds like a Pink Floyd song, with Gilmour’s guitar reaching to the rafters and Waters’ bass getting tangled with Mason’s drums, instead of just keeping time with a piano and Michael Kamen’s orchestra. But before long, we return to Roger’s ho-hum melodicism and pitch-black humor, as he theorizes about applying Nazi tactics to ’80s world leaders.

132. “Signs of Life,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

This solid, if relatively staid, table-setter is kind of like the start of “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” updated (downgraded?) for the ’80s. There’s the familiar liquid silver droplets of Gilmour’s guitar and an enchanting misty ambience, but also synths on synths on synths on synths. If “Signs of Life” had more life and less signs, perhaps Floyd’s first instrumental since the '70s would be more memorable.

131. “Pow R. Toc H.,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

Syd Barrett makes his first appearance on this list courtesy of the lesser of two Piper instrumentals. Syd and his Floyd bandmates make silly noises that resemble percussion before the bulk of the song rides the ups and downs of Wright’s piano playing. This is screwing around in the studio circa ’67.

130. “The Final Cut,” The Final Cut (1983)

On this Wall leftover, the Waters-led Pink Floyd retreads “Comfortably Numb,” only with a more irritating vocal from Waters, a less interesting guitar solo from Gilmour and boatloads of more self-pity. Elsewhere on the album, Waters empathizes with veteran victims and excoriates power-hungry prime ministers, but here he’s worried that his wife is going to tell all to Rolling Stone magazine.

129. “Absolutely Curtains,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

The closer for Pink Floyd’s second soundtrack album for director Barbet Schroeder incorporates the film’s New Guinea setting by gently transitioning from a restless instrumental into a chant by the Mapuga tribe. The latter is more interesting than the former.

128. “A Great Day for Freedom,” The Division Bell (1994)

Not to be outdone by Waters’ cynicism about world politics, Gilmour (with help from future wife Polly Samson) takes a pessimistic glance at post-Soviet Europe. The critiques are fair, but the song’s a gray-colored drag that can’t even be saved when Gilmour trades microphone for guitar.

127. “Burning Bridges,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

This gossamer fluffball is one of only a few Floyd tracks credited to Waters/Wright, but it’s not a great showcase for either’s talents. The organ-fueled melody just hangs in the humid air while listeners are meant to contemplate these sub-high-school poetic musings (“Magic vision stirring / Kindled by and burning / Flames rise in her eyes”). The pairing of Gilmour and Wright’s airy voices makes it sound more profound.

126. “Mudmen,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

But it turns out that “Burning Bridges” is better when you remove the words entirely to allow Gilmour’s needle-nosed guitar to do loops around washes of Wright’s organ playing. If “Mudmen” still moves like it’s slogging through the mud, it’s a more dramatic and interesting track than its partner.

125. “Lost for Words,” The Division Bell (1994)

The penultimate Division Bell track has an appealing rootsiness, sauntering pace and acoustic guitar work from Gilmour. The lyrics (by Gilmour and Samson) start by being centered on forgiveness and bestow a warning against devolving into a “fever of spite,” but end with a recounting of the guitarist’s attempt at reconciliation being rudely rejected by his enemy (Waters). So, really, it’s Gilmour’s self-serving message to Floyd die-hards desperate for a full-bore reunion: “See? I tried. Blame him.” Ahh, forgiveness.

124. “Outside the Wall,” The Wall (1979)

After nearly four sides of vinyl brimming with anger, sadness, misogyny, fascism, war and mental illness, here’s Roger Waters’ spoonful of sugar to balance all that ugliness. And it’s really only a spoonful – a hushed minute-and-a-half featuring all the Whos down in Whoville as they sing their song about futile devotion to love and care. Well, it’s better than nothing.

123. “Give Birth to a Smile,” Music from The Body (1970)

The other members of Pink Floyd went uncredited on this tune that finishes Waters’ soundtrack collaboration with Ron Geesin. But with Gilmour, Wright and Mason present, it counts as an overlooked – but not particularly amazing – Floyd track. The lyrics are pretty hippy-dippy (you can tell from that cringeworthy title), but the fruitful mix of the band’s sound with soulful female vocalists would be a trick worth repeating.

122. “The Trial,” The Wall (1979)

There’s nothing (no, not even the disco beat) less Floyd-ian on The Wall than this showtune-y climax written by Waters and producer Bob Ezrin, better suited to Ezrin’s showbizzy pal Alice Cooper than Pink Floyd. While there’s hardly anything rock ’n’ roll about this operetta, Waters’ vocal performance is incredible, transitioning effortlessly between characters and accents as he depicts the madness in Pink’s head.

121. “Paranoid Eyes,” The Final Cut (1983)

Another Final Cut song, another ballad that lacks dynamism (as well as the participation of any other member of Pink Floyd). “Paranoid Eyes” may be musically dull, but Waters paints a striking portrait of shell-shocked veterans suckered in by glorious war stories, who now put on a different kind of armor to endure their “haze of alcohol soft middle age.”

120. “Wearing the Inside Out,” The Division Bell (1994)

This deliberately paced (almost seven-minute) ballad hews a little too close to smooth jazz, but Richard Wright’s lead vocal – his last on a Pink Floyd album – is earnest and sweet. The words aren’t his (the music is, and Anthony Moore wrote the lyrics), but you’d never know it from the way Wright gently sings about “creeping back to life.”

119. “The Gnome,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

Syd Barrett’s childlike approach to songwriting was often delightful, but it’s a tricky balance between silly and stupid. This tuneful Piper track about a wine-swilling gnome named Grimble Gromble burrows into the latter end, failing to add extra layers to this barely-a-fairy-tale.

118. “Unknown Song,” Zabriskie Point soundtrack re-release (1997)

This pleasant, rustic instrumental is laced with some unusual touches – such as Waters’ insistent bassline (to be re-used in the “Atom Heart Mother” suite) and unsettling splotches of Gilmour’s space effects. They keep things interesting.

117. “Side 3: The Lost Art of Conversation/On Noodle Street/Night Light/Allons-y (1)/Autumn ’68/Allons-y (2)/Talkin’ Hawkin’,” The Endless River (2014)

The least impressive suite of material on The Endless River, Side 3 is not without its charms: Chief among them is “Autumn ’68,” which spotlights a snippet of Wright’s organ playing from the early days of the band – and carries a title that’s a nod to his lovely song, “Summer ’68.” If the bookends of “Allons-y” are “Run Like Hell” soundalikes, they certainly sound distinctively Floydian.

116. “Speak to Me,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

This is hardly a song, but it is a strange sort of overture that subtly previews much of what’s to come on Dark Side (clattering money, crazy laughter, ticking clocks). Of course, the “heart beat” is the most distinctive element, connecting the LP’s first and last tracks to fashion an infinity loop of human experience.

115. “It Would Be So Nice,” single (1968)

In the immediate aftermath of Syd Barrett’s separation from Pink Floyd, the remaining members tried to mimic his knack for melodic whimsy. Wright took a shot on this ’68 single, an irritatingly precocious pop record that made Floyd sound like a third-rate Hollies.

114. “Cirrus Minor,” More (1969)

The bird sound effects are unnecessary and the lyrics are uninteresting, but there’s a great moment in which Richard Wright’s Hammond organ collides with his overdubbed Farfisa and the sound unlocks a ghostly, psychedelic realm.

113. “When You’re In,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

This circular – or maybe just repetitive – instrumental jam is short and forgettable, but the tandem crunch of Gilmour’s guitar and Wright’s keyboards sure satisfies.

112. “One Slip,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

Could a recording sound any more like 1987? Between the video arcade’s worth of bleeps and the dreaded Chapman Stick, the melody of “One Slip” (written by Gilmour with Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera) shines through the “modern” sheen. The cliche-riddled lyrics still ring hollow, however, and “whirled without end” is an unforgivable pun.

111. “Corporal Clegg,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

Another recording that dates from Floyd’s uneasy transition from a band under Barrett’s leadership, the Waters-penned song features a rare lead vocal from Nick Mason, a kazoo played by David Gilmour and bouts of laughter in the backing vocals. It’s kind of fun, which is disturbing for a tune about an unstable veteran (the first hint of Waters’ World War II obsession).

110. “The Show Must Go On,” The Wall (1979)

The song that begins The Wall’s end run was supposed to feature the Beach Boys; instead Pink Floyd landed off-and-on Beach Boy Bruce Johnston and Toni Tennille (but not her “Captain”). Regardless, the California chorus sounds perfect for this easy listening parody, and makes the story’s upcoming fascist fantasies sound even more terrifying.

109. “The Hero’s Return,” The Final Cut (1983)

Even if it’s more sonically exciting than half of the tracks on The Final Cut, “The Hero’s Return” still sounds like the disjointed Wall leftover that it is. Like “One of the Few,” Waters uses the song as backstory for his war-veteran school teacher and the desperate memories that made him a broken man.

108. “Is There Anybody Out There?,” The Wall (1979)

If there’s a great guitar part on a Pink Floyd track, you can almost always credit David Gilmour, but not this time. It’s session musician Joe DiBlasi who plays the prickly classical guitar that enhances Pink’s suffocating isolation behind his emotional wall.

107. “Side 2: Sum/Skins/Unsung/Anisina,” The Endless River (2014)

For the first time since the ’70s, Mason gets to let loose on a Pink Floyd record. His percussive contributions to “Skins” (essentially a long solo) and the propulsive “Sum” are welcome additions to instrumentals that so often find his bandmates completely content to glide along.

106. “Green is the Colour,” More (1969)

Written by Waters, sung by Wright and inspired by Ibiza (the setting for the film More), “Green is the Colour” is the kind of pretty ballad that probably took more thought and work than its easy-going nature would have you expect. But does the tin whistle have to be there?

105. “One of My Turns,” The Wall (1979)

The song highlights the manic depression of main character Pink by moving from a blurry drone to a full rock track as if switching on a light. Waters’ strident vocal matches Pink’s unhinged temper in a manner that splits the difference between annoying and arresting (unlike lesser portions of The Wall, when it’s just the former – or better songs, when it’s simply the latter).

104. “Atom Heart Mother,” Atom Heart Mother (1970)

This might be the Floyd’s longest (continuous) musical suite, but it’s far from their best. The extra orchestration – brass, cello, choir – adds grandeur, but not style. Sure, it’s big and sweeping, but this kind of thing was better left to the Moody Blues. There’s more excitement in one of Richard Wright’s Dark Side keyboard flourishes than in all 23-plus minutes of this bad mother.

103. “The Gold It’s in the…,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

The members of Floyd can rumble along when it suits them, but this chunk of boogie rock sounds as stilted as a suburban middle-school choir trying to sing gospel. The rhythm is forced and Gilmour’s vocal phasing awkward; the complete opposite is true of his extended, snarling guitar solo.

102. “Julia Dream,” b-side (1968)

Some trivia: “Julia Dream” is one of three early Pink Floyd songs to mention an eiderdown, a type of quilt. This b-side is the least compelling of the trio, a fluffy love fantasy written by Waters, influenced by Barrett (why is there an armadillo in this dream?) and sung by Gilmour – the new member’s first lead vocal on a Floyd recording.

101. “Crumbling Land,” Zabriskie Point soundtrack (1970)

Pink Floyd aren’t much of substitute for Crosby, Stills and Nash...

100. “Stay,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

... and they’re not much better at replacing Can’t Buy a Thrill-era Steely Dan.

99. “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 3),” The Wall (1979)

The most abrasive installment of “Another Brick in the Wall” is also the least interesting from a musical and thematic perspective. The pulsing synthesizer and discordant guitar mirror Pink’s anger, and the track is short enough to move us toward the start of Disc 2, where more interesting songs await.

98. “Embryo,” Picnic: A Breath of Fresh Air (1970)

Recorded in 1968 and offered on a multi-artist compilation in 1970, “Embryo” didn’t see release on an official Pink Floyd album until the 1983 collection Works. It’s simple to understand why. This is the kind of psych-folk that the band could turn out without thinking. As such, it became the foundation for a harder-edged jam at 1970-71 concerts, which expanded the dour tune past 12 minutes.

97. “On the Turning Away,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

It’s got a languid pace, but the melody is sound, Gilmour’s vocal is understated and sweet and the song’s message against self-involvement remains relevant. But if you just want to hear David stretch out guitar, that half of the song is solid, too.

96. “The Gunner’s Dream,” The Final Cut (1983)

Roger Waters’ sonic melodrama rises to the message on “The Gunner’s Dream,” which recounts the vision of a gunner on a World War II bomber as he floats down to the carnage below. Before he meets his end, he wishes for a more peaceful, open world, one that the songwriter sings about sensitively and sadly – as if it may never be realized.

95. “Coming Back to Life,” The Division Bell (1994)

Gilmour has many strengths, but lyrics are not one of them – which is why he so willingly accepted the help of his girlfriend-turned-wife Polly Samson on Pink Floyd’s last two albums (as well as his solo discs). He gets off a few good lines without her help on “Coming Back to Life,” which was written about (and not with) Samson. The song is a lovely tribute and, even if it’s a little bit “lite rock” by Floyd standards, Gilmour delivers a glistening guitar break.

94. “The Scarecrow,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

Barrett marries a ricky-tick children’s song aesthetic with existential comparisons between his mood and that of a scarecrow. When it turns out old Syd is doing better than a inanimate object, Pink Floyd celebrate with a baroque finale.

93. “Southampton Dock,” The Final Cut (1983)

Devoid of Waters’ hideous shrieking, and loaded with little details, “Southampton Dock” is a quiet moment that allows its songwriter the space to unfurl (and not expectorate) his perspective. A woman who witnessed the “war to end all wars” again stands at a dock, waving goodbye to a new generation of young men who might never return. The uncertainty and sadness is all the more potent for being set amid gentle orchestration.

92. “Nervana,” The Endless River (Deluxe Edition) (2014)

There’s nothing gentle about this Endless River bonus track, which bares the kind of teeth so much of the rest of the album lacks. It sounds like a well-mannered version of Neil Young and Crazy Horse (rather than the title-referencing grunge greats), and Gilmour and pals sure seem like they’re having fun grinding away.

91. “Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

In terms of Roger Waters’ songwriting, this is positively prehistoric. His first Floyd composition is a bizarre freak-out of jagged instrumentation and crazy phrases (“Gruel ghoul, greasy spoon ...”). The song gets by on the exuberance of young musicians bashing it out in the studio.

90. “Cluster One,” The Division Bell (1994)

Pink Floyd were nothing if not masters of the slow build, the tantalizing pace of instrumental anticipation. Even late in the game, they could deliver an intriguing setup, such as this Division Bell opener that rises from the crackling sound of solar wind to a casual back-and-forth between Wright’s piano and Gilmour’s guitar to a steady procession layered with foreboding.

89. “Take it Back,” The Division Bell (1994)

A breathy vocal performance, some terrific guitar sounds, a set of (gasp!) un-embarrassing lyrics about the environment and a memorable hook make for a pretty good lead single from The Division Bell. If “Take it Back” sounds a little slick and radio-ready for a prog rock band, well it’s not like Pink Floyd were ever allergic to the Billboard charts.

88. “See-Saw,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

Richard Wright’s woozy daydream of a song is a placid piece of psychedelic pop. “See-Saw” moves like molasses as it envelops you in its decadent, descending swirl of mellotron, xylophone and fey vocals. The subject matter – the power balance between a brother and sister – is curious but not captivating.

87. “In the Flesh,” The Wall (1979)

The double LP’s other “isn’t this where we came in?” moment circles back to the album’s opening song, led by the same, explosive volley of organ that transitions into that monster guitar intro. Despite signaling a key moment in The Wall’s storyline (an off-kilter Pink thinks he’s a dictator at a fascist rally), the second iteration of “In the Flesh” is less potent, partially because of extended running time means a loss of urgency. Waters may be in character as he discriminates against members of the audience, but it’s beyond the realm of believability that a Pink Floyd fan is castigated for smoking a joint.

86. “Marooned,” The Division Bell (1994)

It’s not really a song; it’s a five-minute guitar solo. But it’s a good one from Gilmour, with solid assists from Wright and Mason among others, and an epic sound that almost recalls Floyd’s ’70s glory days. One niggling regret: Rick should have played an actual piano on the track. The “synthesizer on piano” setting was beneath someone of his talent.

85. “Nick’s Boogie,” London ’66-’67 (1995)

This spaced-out pre-Piper jam was recorded for the the 1967 film Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, but didn’t make the cut for the soundtrack (“Interstellar Overdrive” did) and finally saw official release decades later. There’s no boogie here, just a fairly engrossing improvisational melange of rubber band guitars and disconcerting organ sounds held together by Nick Mason’s drumming. Far out.

84. “Grantchester Meadows,” Ummagumma (1969)

At the time, Waters was fascinated with making something rhythmic or musical with non-traditional sounds. Less experimental, but more listenable, than his other Ummagumma piece (“Several Species …”), “Grantchester Meadows” places a folk ballad about nature on top of sounds from nature. The buzzing-chirp of a skylark loops its way through the song, which features a pseudo-tongue-twister in the chorus: “Hear the lark and hearken to the barking of the dog fox.”

83. “High Hopes,” The Division Bell (1994)

Self-consciously styled by Gilmour and Samson to be Pink Floyd’s parting shot (it wasn’t, because of The Endless River, which gets its title from a lyric here), “High Hopes” makes a melancholy return to the singer-guitarist’s pre-Floyd days in Cambridge. It also seems to reference the band’s massive success both in the lyrics and in an instrumental section that nods at “Welcome to the Machine.” There’s a dark, sweeping majesty to the song, but it’s more than a little dreary as a capstone. Regardless, “Louder than Words” did it better, and sweeter, 20 years later.

82. “San Tropez,” Meddle (1971)

This little jazzy shuffle isn’t going to win any commendations for profundity, but, man, if it doesn’t capture a mood. From Waters’ easy-rolling croon to Wright’s plucky piano to Gilmour’s shimmering slide work, everything on “San Tropez” adds up to a breezy day on the French Riviera. The lyrics about sand, waves and champagne are almost superfluous.

81. “Side 1: Things Left Unsaid/It’s What We Do/Ebb and Flow,” The Endless River (2014)

Gilmour and Mason’s album-length tribute to the late Richard Wright begins with an archival sound clip of the keyboardist speaking about the communication issues between members of Pink Floyd, before showing evidence of the guys’ abilities to communicate with their playing. This instrumental suite, which purposely recalls “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” in the middle, is as much a tribute to Wright as it is to the unique collaboration between these three Floyds.

80. “Candy and a Currant Bun,” b-side (1967)

When the record company men demanded that he discard the drug references in this song (first titled “Let’s Roll Another One”), Barrett complied, but also slipped the f-word into the lyrics. Because everyone was focused on the flipside “Arnold Layne,” the profanity on this gangly, sex-minded tune passed by the censors. Though tuneful and amusing, it’s a lesser work of the Syd era.

79. “Crying Song,” More (1969)

Sure, crying is mentioned in this ballad’s cryptic lyrics, but the tears worth remembering come from Gilmour’s slippery guitar in the song’s outro. Pink Floyd make a slow, simple folk ballad sound otherworldly by way of Wright’s echoing vibraphone and a dissonant chord in the Waters-penned progression. The result is halfway between dreamy and nightmarish.

78. “Poles Apart,” The Division Bell (1994)

Is there any band more obsessed with their former members than Pink Floyd? It’s not like the Rolling Stones wrote a bunch of songs about Brian Jones in the ’70s. But even 25 years after he replaced Barrett in the Floyd, Gilmour was still singing about Syd (not to mention Roger, in verse two). Unlike some of The Division Bell’s nastier material, the acoustically rooted “Poles Apart” seeks sweetness in the sadness, expressing admiration for – and not just frustration with – Dave’s old mates.

77. “Remember a Day,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

The song’s great, ramshackle drum pattern wasn’t played by Mason (who couldn’t crack it), but by producer Norman Smith. Barrett makes one of his last Floyd appearances by playing the slip-and-slide guitar in the background, although his influence on Wright’s childhood-focused lyrics is a more substantial contribution to the wistful tune.

76. “Waiting for the Worms,” The Wall (1979)

The best extended use of the “Beach Boys” aesthetic comes across here, where it stands it blissful contrast to Waters’ Holocaust-referencing megaphone barking and Gilmour’s malevolent “Another Brick in the Wall” guitar pattern. The sweet-and-sour vocal interplay between Gilmour and Waters is disconcertingly effective, with each of them delivering dark ideas in completely different tones.

75. “Paint Box,” b-side (1967)

The flipside to “Apples and Oranges” owes a bit to Sgt. Pepper, but its importance in the Floyd canon is the use of an Em(add9) chord, which might as well be the band’s signature chord (for all of the times it appears in their more famous songs). Though less-known, Richard Wright’s “Paint Box” has its pleasures, from an impatient rhythm to ricky-tick piano to frenetic drum fills from Mason.

74. “The Narrow Way (Parts 1-3),” Ummagumma (1969)

Of anyone in the band, Gilmour had the most trepidation about creating an individual experimental piece for the studio disc of Ummagumma. And he ended up with the best thing on that half of the project. The three-part suite repurposes an existing tune for the rustic opener, but Gilmour’s guitar steamrolls through the middle portion before landing on a George Harrison-ish bit of space-twang for the climax.

73. “The Happiest Days of Our Lives,” The Wall (1979)

Whether this reflects Pink’s or Roger’s opinions on mothers or wives, it’s troubling that there’s always a woman to blame for the mental issues explored behind The Wall. Even the bullying teachers’ behavior gets chalked up to their “fat and psychopathic wives” on this track, which is really an extended intro for “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2).” But what an intro, with the sounds of ominous helicopter and vicious cackling, Waters’ poison poetry and Mason’s thunderous transition of a drum solo.

72. “Biding My Time,” Relics (1971)

OK, so here’s the exception to the whole notion of “Pink Floyd are boring when they play a straight blues tune.” Waters writes ho-hum lyrics to a striptease beat, but that doesn’t matter because he quickly has the spotlight snatched from him by his bandmates. Wright blurts like a maniac on the trombone before getting greasy on the organ, Gilmour unleashes his inner Chicago bluesman on a spindly guitar solo, and Mason pounds his drum kit until it’s six feet under.

71. “Side 4: Calling/Eyes to Pearls/Surfacing/Louder than Words,” The Endless River (2014)

Side 4 of The Endless River is no more or less exciting than the other side’s instrumental meanderings, with the exception of the final portion – the only true song on the record. With lovely lyrics by Gilmour’s wife Polly Samson, inspired by her observations at the Live 8 reunion, “Louder Than Words” presents the special symbiosis between these musicians. It’s a nice final bow.

70. “If,” Atom Heart Mother (1970)

Waters grabs an idea from Rudyard Kipling and delivers a pleasant bit of pastoral introspection. The singer’s climbing bassline and Gilmour’s tangy slide guitar come along just before “If” would have gotten stuck in a folksy rut.

69. “Main Theme,” More (1969)

Some mind-altering psychedelic soundtrack work from Floyd, back in the days where the experiments could go one way or the other. This one goes right, with the help of Wright’s restless keyboard playing and Waters’ Whac-a-Mole bassline.

68. “Ibiza Bar,” More (1969)

Every so often, Pink Floyd let their hard-rock flag fly. This time around, the buzz-and-clatter is satisfying (although not as dynamic as “The Nile Song” from the same album). And the lyrics aren’t dumb. Gilmour gives voice to artistic creations that come to life and beg their artists for a friendly setting and a happy ending.

67. “Obscured By Clouds,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

One giant, gnarly buzz begins the Floyd’s final soundtrack album and persistently rumbles throughout this leadoff track. Meanwhile, Mason combines two separate beats into a highway rhythm and Gilmour plays mirror games in the left and right channels, stringing along telephone wires of acidic guitar on the way.

66. “The Thin Ice,” The Wall (1979)

Many of The Wall’s better moments bring together the double album’s two lead singers in a balance of sweet (Gilmour) and sour (Waters). After the overture, the main story begins here, with Gilmour’s gentle, parental cooing in the first verse, followed by Waters’ silver-tongued cynicism in the second. If the “thin ice” is one metaphor too many on an album that has its hands full with one big, blocky metaphor, the swaying guitar solo sounds good.

65. “Country Song,” Zabriskie Point soundtrack re-release (1997)

Pink Floyd have more folk and country in their bones than some might expect. Of course, this “country” song quickly moves into proggy territory with a deliciously rude raspberries of electric guitar and a high-concept story that takes place on a chess board. That’s right, Floyd beat Yes to recording a chess-themed song by at least a year – even if this rendition didn’t see official release until decades later.

64. “A Saucerful of Secrets,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

The members of Pink Floyd had only just stopped trying to mimic Barrett’s twee-pop sensibility when they lurched in a completely different direction with this heady, four-part suite. There’s enough room in the saucer for both chaotic noise and enchanting beauty – a rough blueprint sketched out by Waters and Mason kept it from becoming a formless blob. With distinct segments and epic sounds, the instrumental is the first rung in the ladder that would culminate with the band’s most celebrated LPs.

63. “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 1),” The Wall (1979)

Waters weaves autobiographical details into Pink’s story and begins the “Another Brick …” motif with this track. The lyrics move the backstory along, but the star here is Gilmour’s guitar – or, really, guitars. His reverberating, multi-tracked and muted parts create a schizophrenic environment as the sounds pile on top of one another and a different guitar keeps trotting along.

62. “Cymbaline,” More (1969)

Try as he might, Waters couldn’t match Barrett’s ability to throw together fantastical and humdrum references and reveal a psychedelic dreamscape on the other side of the tunnel. Yet this nightmare (with bongos!) lands on some memorable imagery (“a tube train up your spine”) while exposing the songwriter’s worst fears: heights and ravens, music managers and agents. Plus, as a lead singer, Gilmour’s knack for nuance was already increasing.

61. “Flaming,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

A bunch of drug-induced nonsense from Barrett. But only the most psychedelic-rock-averse listener wouldn’t have a good time with the (literal) bells and whistles of “Flaming.” And there’s that eiderdown again.

60. “Chapter 24,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

Early Floyd owes a fair share to another band that was making famous music on Abbey Road. If John Lennon could crib from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, then Syd Barrett might as well pull from the I Ching, describing a mathematical view of progress on “Chapter 24.” Barrett’s nonchalant vocal delivery coupled with Wright’s majestic swirls of organ makes the theory seem enlightening. Hey, maybe it actually is.

59. “Wot’s… Uh the Deal?,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

A folksy gait, some warm instrumentation, a winning chorus and lyrics that suggest Moses was one weary hippie. What’s… uh, not to like about this overlooked Floyd gem?

58. “Keep Talking,” The Division Bell (1994)

Before you think that it’s insensitive to use a Stephen Hawking sample on a song titled “Keep Talking,” the speechless scientist was the impetus for this Division Bell standout. A British Telecom commercial that featured Hawking’s robotic “voice” so thoroughly moved David Gilmour that he, Wright and Samson wrapped this song about communication around fragments of Hawking’s speech. The other voices on this song – those of the background vocalists as well as Gilmour’s talkbox effect – make a dramatic song into a titanic moment.

57. “Matilda Mother,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

Richard Wright brings some Eastern intrigue to Syd Barrett’s portrait of a child being read bedtime stories (told from the kid’s point-of-view, of course). The keyboardist delivers a serpentine solo in the Phrygian dominant scale – employed in Indian and Klezmer music, among others – and gives the lead vocals a dreamy, stately grace.

56. “Apples and Oranges,” single (1967)

Even a seeing a pretty girl at the supermarket is a psychedelic experience for Syd Barrett, who conjures this gonzo song out of things as mundane as, well, apples and oranges. The single, which flopped big-time, struts on the verses – then gets lost in a daydream on the choruses. Barrett defies musical expectations from line to line, as he’s somehow able to cram in too many words here and stretch too few words there. You never know what’s next; but it’s a joy when it arrives.

55. “On the Run,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

Just because it’s not one of Dark Side’s all-stars doesn’t mean that this travel sequence isn’t fascinating. “On the Run” is a headphone experience of the highest order, in which crazy laughter, frantic footsteps, whooshing cars and crashing planes are all twirled – like strands of spaghetti – around the back-and-forth of an eight-note synthesizer loop.

54. “Young Lust,” The Wall (1979)

This song (one of three on the double LP written by Waters and Gilmour together), reflects the lusty self-destruction of the main character via a dirty, blues-rock ditty. On first listen, “Young Lust” might seem too dumb for a band of this caliber, but between its narrative purpose and Gilmour’s sharp strains of guitar and bellowed vocals, it wins you over.

53. “Free Four,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

This folk-rock toe-tapper becomes distinctively Floydian with its steady rumble of VCS3 synthesizer, almost incongruous rock guitar solos and morbid observations by singer and songwriter Waters. He fixates on death, regret, his father and the music industry (all themes that would appear again soon in the band’s more renowned albums), but belies all the darkness with the “Free Four”s jaunty bounce.

52. “Sorrow,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

Time has not been kind to Pink Floyd’s ’80s reboot – a David Gilmour solo album in all but name. But if you can get past the shoulder-pad synthesizers and the effects that put distance between the listener and Gilmour’s guitar, “Sorrow” rewards the effort. The lyrics, inspired by John Steinbeck, are arguably David’s best, circling a broken man dismayed by an even more broken world. The potent solos that open and close the song suggest a grim, unending struggle.

51. “The Nile Song,” More (1969)

Just because there’s no room for Wright on this track doesn’t mean that it’s wrong. On this most muscular of Pink Floyd songs, Gilmour roars on vocals and squeals on guitar, Waters assaults his bass and Mason kicks everything forward with his drums. They could have been a damn fine power trio if the whole concept album thing didn’t pan out.

50. “Goodbye Blue Sky,” The Wall (1979)

By this time, Pink Floyd were masters at using the VCS synthesizer to create a terrifying drone – here meant to stand in for the Luftwaffe blitzing Britain in Pink’s memory. Gilmour’s beautiful performance, subdued vocal and restless guitar are the humanity that survives in between the destruction. But even the survivors don’t get away unscathed, as the song suggests: “the pain lingers on.”

49. “Point Me at the Sky,” single (1968)

Everything shifts on this wacky, space-age tune – which is more Georges Melies than NASA. The mood oscillates between dreamy calm and fiery rock, the vocals flip between co-writers Gilmour and Waters, and the lyrics change from first-person to third. Even time appears to drift between the present (in which our hero is only too happy to escape the Earth) and the future (in which he’s sick of eating his capsules for dinner). The funny, thrilling single flopped, only to become a rarity until the compact-disc boxed set era. Garnering a larger reputation was its b-side ...

48. "Careful with that Axe, Eugene,” b-side (1968)

Between the hint of violence in the song title (whispered as a wild-eyed warning during the otherwise instrumental track) and the slowly encroaching tangle of Pink Floyd’s post-psych free-for-all, “Careful with that Axe, Eugene” is a sinister bit of sludge coughed up from the underworld. This little demon creeps along, builds in volume, makes its menacing stand and, finally, slinks away into the darkness to find new prey.

47. “A Pillow of Winds,” Meddle (1971)

What could be construed as a simple folk song is rich in detail. The key switches from E major to E minor to reflect the (literal) darkness of the lyrics. Waters creates a drone on a fretless bass. And Gilmour layers guitars upon guitars (acoustic, electric, slide, pedal steel …) to spin a spiderweb of sound. Plus, it’s the last song in the eiderdown trilogy.

46. “Any Colour You Like,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

Providing much more than breathing room between “Us and Them” and Dark Side’s big finish, this three-and-a-half-minute instrumental features rain showers of Wright’s synthesizer playing, looped in beautifully disorienting fashion. Then, Gilmour hijacks the proceedings with a couple minutes of shimmering guitar, playfully overdubbed so that the solos “bawk-bawk” at each other like cranky chickens. The sonic transitions in and out of “Any Colour You Like” only enhance the songs that surround the track.

45. “Your Possible Pasts,” The Final Cut (1983)

Of all of the mopey Wall leftovers that appear on The Final Cut, “Your Possible Pasts” is the best for a number of reasons. The loud-quiet-loud tactic is not only dynamic, but jarring – even when you know when the snare shots and organ swells are coming. The chorus (“Do you remember me? How we used to be? Do you think we should be closer?”) aches with humanity. And the wartime imagery – railway cars and good-time girls covered in the brown grime of tragedy – is 10 times more interesting than Waters yapping at Margaret Thatcher.

44. “Come in Number 51, Your Time is Up,” Zabriskie Point soundtrack (1970)

For the finale of Antonioni’s film, Floyd re-recorded “Careful with that Axe, Eugene” but with enough alterations – beyond the new title – for it to qualify as a different track. The key is changed, there’s a choir and more screaming (Waters’ bone-chilling speciality) and the explosive second half comes on like a summer heat storm, as opposed to the gradual build of the original. Positively volcanic – and even better than “Eugene.”

43. “Pigs on the Wing (Part 1),” Animals (1977)

It’s no secret that love songs are not Floyd’s (and certainly not Roger Waters’) strength. Animals’ acoustic bookends don’t celebrate love as much as classify it as a better alternative to the miseries of modern life. Sonically simple (just voice and guitar), "Part 1" can be praised for its brevity and lightness in introducing the album’s gloomy concept.

42. “Pigs on the Wing (Part 2),” Animals (1977)

"Part 2," although sounding nearly identical to its first half, gets the edge because of how expertly Waters wraps up this dense, complicated album. Love conquers his dog-like ways and the clouds part to reveal something akin to hope. A happy ending on a Pink Floyd album? When pigs fly.

41. “Learning to Fly,” A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

The song’s mechanical ’80s crunch (created by collaborator Jon Carin) is irresistible, as are David Gilmour’s smooth-soaring vocals on this first post-Waters Pink Floyd hit. Is the subject of “Learning to Fly” as basic as the title suggests (both Gilmour and Mason are hobby pilots)? Or is the track a metaphor for Gilmour’s new role as Floyd’s undisputed leader, or even a rumination on souls departing this world? The answer is open to interpretation, which probably means the lyrics are well-chosen.

40. “Not Now John,” The Final Cut (1983)

It’s almost as if, deep into his work on The Final Cut, Waters remembered that satire could be fun (and that music could be exciting). He also seemed to recall that Gilmour was just sitting there on the bench. David makes the most of his game time on the rocking “Not Now John,” ferociously tearing into lyrics that are a head-spinning mix of Waters’ personal and political demons come to life. For those who tut-tut at the song for being boorish, it’s a shame they can’t bask in the pleasures of this buzz bomb, complete with female backing vocalists screaming “fuck all that.”

39. “Let There Be More Light,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

Wright and Waters play the chanting druids foretelling of an epic meeting between aliens and earthlings while Gilmour blazes in on the choruses to narrate a close encounter that occurred (at least, according to this song) at Mildenhall. This is fun, fantastic space rock in which the alien takes the form of “Lucy in the Sky” and squalls of organ herald a new era for the human race. Then, Gilmour lets the psychic emanations flow from his guitar – the axeman’s first solo on a Floyd record.

38. “Fat Old Sun,” Atom Heart Mother (1970)

For his solo contribution to Floyd’s 1970 LP, Gilmour penned a tribute to the clear, calm wonders of the countryside. The nature-focused poetry is nice, and David’s high voice is angelic, but “Fat Old Sun” really takes off when the words end and Gilmour’s guitar takes over. His ascending, fizzing lines shoot out of the stratosphere to his sunny subject, who has a great gig in the sky. But, unlike Icarus, the guitarist returns safely from his journey.

37. “Hey You,” The Wall (1979)

With few exceptions, Pink Floyd are at their best when they collaborate and one member doesn’t dominate too much. Even though “Hey You” (like so much of The Wall) is the creative vision of Waters, it wouldn’t have achieved its uneasy mood without his bandmates. Gilmour doesn’t just lend his sad-eyed vocals to the first two verses, he delivers the guitar break and plays the song’s distinctive, liquidy bass part. Wright adds midnight cool to the buzzing yearning while Mason gives just enough push, letting his fills tumble like hammers. As Waters cries in the final line: “Together we stand, divided we fall.”

36. “Summer ’68,” Atom Heart Mother (1970)

Wright joins together the best, orchestral touches (big, brassy horns) of Atom Heart Mother’s overstuffed title epic with some of the more pastoral qualities of Waters’ and Gilmour’s solo contributions to create the album’s best song. As such, this track – about Wright’s empty feelings following meaningless groupie encounters – is both gentle and bombastic, calm and upset, simple and baroque. Few “summer songs” are so complicated.

35. “What Do You Want From Me,” The Division Bell (1994)

There is a great moment here (it happens three times, actually) in the pre-chorus, when Gilmour shakes off his subject – rolling his eyes and singing “You’re so hard to please” – as the chords ascend, boosted by a choir of background singers. The band and the women’s voices climb to this pinnacle and then – flash! – Gilmour’s guitar shines down like a lighthouse beam on the choppy waters below. Build and release: A Floyd speciality. The rest of this blues-derived behemoth is pretty wonderful too, mostly because “What Do You Want From Me” has grit. Pink Floyd are not a Swiss timepiece, and some sand in the gears only makes them sound more interesting.

34. “Childhood’s End,” Obscured by Clouds (1972)

Pink Floyd aren’t the Meters, but they can get pretty funky for a bunch of British guys. After a minute-plus of organ drone, “Childhood’s End” fades in with some swagger. Waters’ perpetual motion bass and Mason’s crisp drumming create a vehicle for Wright to paint with wide swaths of Hammond organ and Gilmour to drive with sharp bursts of tightly wound guitar. With its funk-rock strut and widescreen view of humanity, the song serves as a fantastic dry run for the even better “Time.”

33. “Lucifer Sam,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

It’s just a song about Syd’s cat. And yet, under the creative tutelage of Barrett paired with the turbulent power of Pink Floyd, “Lucifer Sam” becomes something like a psychedelic twist on the “Peter Gunn Theme.” The twangy, stair-stepping guitar hook leads to a whirlwind of hyperactive bass playing, abrasive maracas, tart bursts of affected organ and ghostly moans of slide guitar. “That cat’s something I can’t explain.” Fair enough, Sid.

32. “Run Like Hell,” The Wall (1979)

Words by Waters, music by Gilmour: a worthwhile division of labor. This Wall radio staple carries a nasty assembly of threats paired with some of the most scintillating guitar work ever to be featured on a Pink Floyd record. In this band’s hands, a four-on-the-floor beat isn’t an excuse to dance, but motivation to “Run Like Hell.”

31. “Interstellar Overdrive,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

What a mess this could have been. Studio versions of improvisational stage pieces rarely maintain the magic of the moment, but the early Floyd nailed this near-10-minute rendition of their stage favorite freak-out. Starting with that great chromatic progression, “Interstellar Overdrive” then goes wherever it damn well pleases, following Barrett’s metallic screech for a while or dwelling on a bass melody Waters was still working out or hanging with Wright’s keyboard fanfare for a spell. It’s a trip, in all meanings of the word.

30. “In the Flesh?,” The Wall (1979)

An overture as brutal as this rock opera deserves, and more exciting than most of what is to come. “In the Flesh?” erupts with power chords, skyscraper organ, gunslinger guitar and martial drum fills. At the center is Pink, as voiced by Waters, heralding the start of his depressing story with maniacal glee and shouting stage directions, which include dive-bombing the audience. An explosive entrance, to say the least.

29. “Jugband Blues,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

There’s enough material for a psychiatric symposium in “Jugband Blues,” Syd Barrett’s swan song in Pink Floyd. With the former frontman quickly losing his grip on reality (thanks to already existing mental issues and heavy drug use), he seems to put his addled perspective down in a song that changes time signatures, includes a Salvation Army band blasting away and features lyrics such as “I’m obliged to you for making it clear that I’m not here.” It’s amusing, but it’s not a joke. It’s confused, perhaps intentionally. It’s a farewell gesture, or is it? Just as the specter of Syd continued to haunt the Floyd, the murky mysteries of “Jugband Blues” continue to fascinate fans.

28. “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2),” The Wall (1979)

Is this song good in spite of the disco beat or because of it? Does the addition of a child choir repeating the only verse and chorus transform “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)” from a song fragment into a full-blown composition? Is Pink Floyd’s only No. 1 single this high on the list because it’s a great recording, or because it’s merely famous? Do we need an education or is it just thought control? But there’s no question about Gilmour’s great guitar solo.

27. “Mother,” The Wall (1979)

“Mother” features another of David Gilmour’s stand-out solos, but so much more. It’s one of the double-album’s most nuanced tracks, building gently to rise and fall with Waters’ characterization of an overprotective mother, who harms by helping. As such, the recording – and Gilmour’s cotton-soft vocal delivery of the mother’s lines – depicts the inflicted damage without a hint of outrage. Pink’s yielding of adult responsibilities is suggested by shifts in meter. The ground shifts beneath him as his emotional wall rises in front.

26. “Sheep,” Animals (1977)

One of Animals’ three main courses, “Sheep” is Waters’ merciless excoriation of society’s followers – that is, until they briefly turn on their oppressors, only to return to their humdrum lives. If the lyric-writing isn’t razor-sharp, Gilmour’s and Waters’ guitars are. Midway through each verse, the instrument enters like a Jack Nicholson in The Shining, slicing and dicing its way to the next calamity. Gilmour also plays bass here, galloping alongside Nick Mason’s drums while dodging in and out of the way of Richard Wright’s off-kilter organ. The whole ordeal ends in a shower of sparks, a glittering waterfall of jagged guitar that sends the sheeple back home.

25. “The Great Gig in the Sky,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

There is no greater contribution to the Pink Floyd catalog by someone other than a band member, engineer or producer than Clare Torry’s quaking vocal performance on “The Great Gig in the Sky.” Wright came up the beautiful piano and organ progression, but it was hired gun Torry who took the track into outer space. Envisioning herself as an instrument, she somehow merged the blood-curdling terror of shuffling off this mortal coil with the ecstasy-infused pleasure of earthly delights. What soul, what scope, what beauty.

24. “When the Tigers Broke Free,” single (1982)

Rejected by Pink Floyd’s members for inclusion on The Wall, allegedly because it was too personal, Waters’ solemn remembrance of his father’s death instead landed in the film version and, decades later, was inserted into re-releases of The Final Cut. This gradually crescendoing, starkly orchestral song succeeds precisely because it is personal. Roger recounts the tragic end of the Royal Fusiliers Company Z during World War II and, in so doing, makes the cost of war achingly human. His yelping voice may never have been put to better use that the tune’s closing verse, which boils over with anger as Waters declares, “And that’s how the high command took my daddy from me.”

23. “Nobody Home,” The Wall (1979)

There are a lot of big elements on The Wall – larger-than-life characters, epic guitars, overblown orchestrations and screaming vocal performances. Which makes the quiet, sensitive song “Nobody Home” all the more valuable. Drawing on both his own feelings of rock-tour-alienation and what he witnessed of Syd Barrett’s mental break, Waters takes stock of all the meaningless stuff in Pink’s life and places them in vivid contrast to what’s missing. It’s a somber, but sweet piano ballad (that gets the strong urge to fly, down the stretch) that brings the rock opera back to a human scale. And it’s got a perfectly placed Gomer Pyle cameo.

22. “Arnold Layne,” single (1967)

At a tidy three minutes long, “Arnold Layne” is a world away from the jammed-out live version (and a whole universe removed from the Floyd’s ’70s aesthetic). But the band’s debut single established Syd Barrett’s melodic ability and curiosity for fringe characters – such as “Arnold,” a transvestite who snags women’s clothing from backyard laundry lines. The pop gem is weird, catchy and psychedelic in its use of echo and Wright’s organ break. Although Pink Floyd would morph a time or two in their run, the first version of this band was pretty potent.

21. “Eclipse,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

Repeat listens to Dark Side and decades of rock radio have conditioned listeners to think of “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse” as one song, but they were written at different times and are separate tracks, so they deserve to be assessed as such. Though not quite as brilliant and thrilling as its brother, “Eclipse” is a phenomenal finale, doing lyrically what “Speak to Me” did with sound effects: referencing nearly all of this LP’s components. In just over a minute, Waters reels off a litany of all-encompassing lines (all, everyone, everything …) that summarize the light and dark elements of life as a human being. Washes of Wright’s organ and echoing background vocals enhance the big finish. Pink Floyd stick the landing, as the song fades back into a quiet heart beat.

20. “Welcome to the Machine,” Wish You Were Here (1975)

Studio shenanigans at their finest. Whether Waters’ song is about the “machine” of the music industry or a dystopian, machine-ruled society, the track’s human/mechanical dichotomy is personified by Gilmour. Not only do his warm-blooded acoustic guitars strum amidst invasive and bloodless synthesizers, his lead vocal is treated to sound like an emotionless, robotic overlord – a ghost in the machine. “Welcome to the Machine” squeezes gallons of unease from its terse lyrics while making the most out of every tick, buzz, thump and hum. The layers of sound are so skillfully realized, it’s like the song was recorded in 3D.

19. “Fearless,” Meddle (1971)

What’s the best thing about “Fearless”? Is it Gilmour’s honey-hushed vocals or his jangle vamping on electric guitar? It is Waters’ simple poetry or Mason’s strange rhythm? Is it the wonderful way the acoustic guitars climb the song’s main riff? Is it the bizarre fade-in-and-out of Liverpool soccer fans singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone” (which should be annoying, but somehow adds size to this song)? Or is it the song’s clear, soft and crisp mood, like a deep breath of mountain air, created by all of the above? “Fearless” might be the most underrated song in the entire Floyd oeuvre.

18. “Us and Them,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

There might not be a more gorgeous sound on a Pink Floyd record than when Gilmour’s and Wright’s voices converge on Dark Side’s jazzy ballad. It’s not a roar. It’s not a gasp. It’s just this beautiful exhalation, like they opened their mouths in tandem and this dream of a voice was the result of combining their vocal cords. On a smart song about conflict, it’s a good example of teamwork.

17. “Have a Cigar,” Wish You Were Here (1975)

Waters has said he regretted the decision to ask Roy Harper to sing lead on this classic, because he played the lines for laughs instead of sniveling commentary. But for a band that lacked for humor after Barrett left (with the exception of Waters’ dark sarcasm), “Have a Cigar” is an oasis of fun in a sea of seriousness. While Waters’ string-bean bass and Gilmour’s telephone cord guitar tangle themselves into a funk-rock mass of sinew, Harper interprets his record executive as a buffoon, a clueless cartoon of avarice and empty encouragement. Roy’s performance doesn’t make the Waters-written caricature any less deplorable, but it’s more entertaining as a send-up, rather than hearing yet another rock band get bitter about the villains in the industry.

16. “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun,” A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

More trivia: this 1968 song features guitars played by both Barrett and Gilmour, making it the only Floyd track to feature all five of the band’s members. It’s ironic, then, that the guitar parts are barely noticeable on a moody track that spotlights Waters’ Eastern-influenced bass and vocal murmur, Mason’s timpani mallet tribal drumming and Wright’s dancing vibraphone and spooky organ. Inspired by (or ripped off from) Chinese poetry, “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun” finds a dark pocket of the universe and hovers there for as long as it can stay airborne, making it all the more creepy – and alluring.

15. “Breathe,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

If you listen to Pink Floyd’s discography in chronological order, when you arrive at Dark Side, it’s like the band doubles in size. Not in membership or the fullness of the sound, but the scope of this album. They’re working on a bigger canvas, the proportions stretched by David Gilmour’s shooting-star pedal steel in the opening moments of “Breathe.” It’s big but graceful, slow but so richly detailed – like watching Lawrence of Arabia in 70mm. As with the child who enters the world in the song’s first verse, there’s so much to take in here. Yet there’s still room to breathe.

14. “Astronomy Domine,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

“Interstellar Overdrive” and “Astronomy Domine,” Piper’s opening shot, led some to classify Pink Floyd as space rock, a label they resisted. Listening to “Astronomy Domine,” however, you can understand why that tag was such an easy one for fans to affix. Barrett takes listeners not just on a journey to the stars (and the moons of Uranus and Saturn), but to a whole other world with imagery that can’t help but fire the imagination (“the icy waters underground,” “a fight between the blue you once knew”). The sonics are spellbinding, particularly the descending, chromatic progression matched with a piercing howl that could be the sound of a star burning out. But, like Barrett, before it crumbles, it burns so very brightly.

13. “Shine on You Crazy Diamond (Parts VI-IX),” Wish You Were Here (1975)

The second “half” of the band’s tribute to Syd Barrett can’t quite match its counterpart in terms of sweep and substance, but the four-part portion is as varied and compelling as any Floyd recording. The highlights, in order: Waters and Gilmour weave bass guitars into an undulating tapestry, David attempts to break the sound barrier on his lap steel solo, Roger’s vocals return and he pleads to his troubled pal (“Come on, you miner for truth and delusion, and shine”), the boys try on some neon-and-midnight funk with Wright’s clavinet in the foreground, and then the band goes catatonic as Wright pays elegiac tribute to his fallen bandmate on piano and keyboard, quoting the “See Emily Play” melody before the whole dream fades away.

12. “Bike,” The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

Watch a scripted movie or TV show with a child in it and notice how, at least 90 percent of the time, the creators get kids wrong. Invariably, they are more peculiar, lively, funny and interesting than they are portrayed. Barrett gets the kid’s eye perspective perfectly right on “Bike,” from their fascination with details (a basket, a bell and “things to make it look good”) to their humor (“I don’t know why I call him Gerald”) to their curious and generous spirit. The twist is that Syd combines this notion with the idea that he’s trying to wow a woman with an array of things (“if you want things”), drawing a parallel between a child’s need to impress an adult and a young man’s need to impress a potential girlfriend. The whole thing ends in a clatter of cranks and chimes, whistles and thumps – fun for boys and girls of all ages.

11. “Money,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

There is no song in Pink Floyd’s catalog, or anyone’s catalog, like “Money.” Its off-kilter 7/4 time signature, established by a repeating loop of seven clinging, ripping and rattling sound effects, is as distinct a musical signature as any non-musical sound in rock history. Waters makes up for the slightly dotty lyrics by writing an iconic bassline which carries the main section on strings that sound like they’re the size of power lines. Mason does great work on the drums, as does collaborator Dick Parry, who blurts a blood-red tenor saxophone solo. But the special prize goes to Gilmour, who shines on the special 4/4 section of “Money” with not one, not two, but three passes at a guitar solo. He tells a sonic story, shifting from a “live” double-tracked section to a “dry,” sparse portion and roaring back with a blazing, “wet” final round. Then it’s back to 7/4, a delightfully different rhythm for a radio hit.

10. “One of These Days,” Meddle (1971)

Meddle’s first track turns Nick Mason into a monster, employing studio wizardry to make the song’s sole vocal line (“One of these days I’m going to cut you into little pieces”) more garbled and upsetting. But all the Floyd members sound like monsters on this big, bold instrumental, with its twin galloping basses from Waters and Gilmour, lightning strike organ whooshes by Wright and cellar-door batterings from Mason. After Nick’s threat, David kicks it into overdrive, burning down the highway on long stretches of rampaging guitar lines that squeal out past the vanishing point. “One of These Days” is relentless.

9. “Pigs (Three Different Ones),” Animals (1977)

With a repeating hook worthy of becoming an Eric Cartman outcry (“Ha ha! Charade you are!”) and a sneering sentiment from Waters, “Pigs” is all sharp corners and razor edges. Everything is wielded like a weapon, from shards of rhythm guitar, jabbing cowbell, slashing piano slides and, certainly, the vocal delivery by Waters, who spits poison-tipped needles through gritted teeth at the powers that be. In its instrumental break, the song's underbelly is softer, but darker. Gilmour breaks out a snorting talkbox and the rest of the band gets caught in a hypnotic swirl that suggests the disorienting distractions that, in Waters’ view, allow the greedy ruling class to maintain status. You can think about all that nasty business, or just groove along to the jutting rhythm, one of Waters’ most beguiling efforts.

8. “Echoes,” Meddle (1971)

The band spreads way, way, way out on this extended epic – at 23-plus minutes, the length of an entire side of vinyl. It’s not the duration of “Echoes” that’s noteworthy, only that the extra running time allows for such a wealth of noises and ideas. If the early, psychedelic Floyd stuff was “space rock,” this is “deep sea rock,” and just as enchanting. Wright creates a submarine-like “ping” while Gilmour dreams up a pod of whales by plugging a wah-wah pedal in backwards. Mason guides the ever-changing song, and Waters writes of wind, water and, more importantly, humanity. The band believed this mix of outward-looking lyricism and dynamic sounds was the stepping stone to full album suites, like Dark Side. (And, if you agree with Waters, the song’s descending chord motif led to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera.)

7. “See Emily Play,” single (1967)

There are few better marriages of pop single and ’60s psychedelia than “Emily.” Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd packs this catchy tune full of tricks – from the disorienting space-age intro to the buzzsaw guitars to an elfin piano solo (that sounds like Wright recorded it in a dollhouse) to the deep “duh-dunn” that announces each verse – but never strays far from the melody. There’s also some heavy feelings ground into this portrait of a LSD-tripping festival-goer who is content to “borrow somebody’s dreams” and “float on a river, forever and ever.” It’s almost as if Barrett was forecasting his own drug-prompted troubles.

6. “Brain Damage,” The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

Speaking of Syd’s troubles, they were part of the inspiration for Dark Side’s penultimate track, written and sung by Waters. “Brain Damage” is one of the most powerful pieces in the Pink Floyd canon, not only because of those great, dam-breaking crashes of organ and backing vocals on the chorus or the “whistle through the graveyard” guitars, but because of the empathy that pervades the lyrics. As the Floyd’s run progressed, Waters became comfortable looking down his nose at his subjects, even dehumanizing them into “animals” or “bricks.” But here he implicates himself. He counts himself among the lunatics and, in a way, reaches out to Barrett in the song’s final lines: “If the band you’re in starts playing different tunes / I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon.” Of course, both Barrett and Waters would end up on the dark side of Pink Floyd, looking in.

5. “Comfortably Numb,” The Wall (1979)

The Wall is Waters’ show and he wrote the lyrics and some of the music for “Comfortably Numb,” but its greatness belongs to Gilmour. What’s more sublime about his melancholy-turned-fiery contributions? Is it the instant when Gilmour emerges, floating in on the choruses (suggesting a temporary, drug-assisted respite from Pink’s suffocating problems) or the entirety of the guitarist’s two majestic solos (communicating a sadness and anger well beyond the capabilities of the song’s lyrics)? The choruses ache, but David’s second, more combustible solo might provide the only tangible link between sad-sack Side 3 and furious Side 4 of this rock opera. Every note matters.

4. “Dogs,” Animals (1977)

Animals’ best track delivers even more incredible guitar work from Gilmour, who makes his instrument cry and cackle, moan and mock, surge and slice. But this 17-minute leviathan is a brilliant collaboration between Floyd’s members – not just co-writers Waters and Gilmour (who each sing lead for a while), but also Mason (who pounds and cracks his way through the song’s changing tempos) and Wright (who plays no less than five different keyboards to bring a variety of textures to the epic). As lyricist, Waters is in full-on deride mode, as he writes about Machiavellian menace, but the writing is so crisp and clever (“And it’s too late to lose the weight you used to need to throw around”), the scoffing becomes sport.