Why the Beatles’ First Live Album Took Over a Decade to Come Out

The Beatles never released a live album while the band was still together, though it wasn’t for lack of trying.

The Fab Four’s meteoric rise in fame had made them the biggest group in the world. By 1964, Beatlemania had spread around the globe, and the band’s U.S. label, Capitol Records, wanted to take full advantage.

When the idea for a live album was first brought up, producer George Martin wanted to record the band’s Feb. 16, 1964, performance at New York's Carnegie Hall. A dispute with the American Federation of Musicians made such an undertaking impossible, so Martin and the band turned their attention toward a different date on the calendar: the Beatles' first performance at the iconic Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

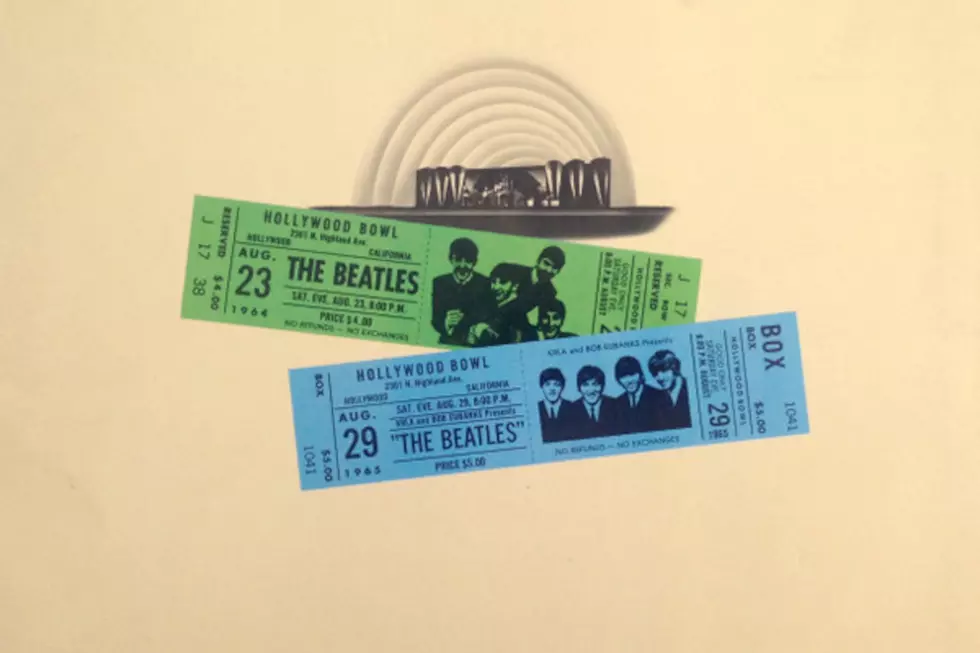

On Aug. 23, 1964, the Beatles played a 12-song set in front of nearly 19,000 ravenous fans. The tape was rolling and the show was good - perhaps too good. The crowd was so enraptured by the Beatles' performance that the recordings were virtually useless, as screaming drowned out the music.

“We recorded it on three-track tape, which was standard U.S. format then,” Martin later recalled. “You would record the band in stereo on two tracks and keep the voice separated on the third so that you could bring it up or down in the mix. But at the Hollywood Bowl, they didn’t use three-track in quite the right way. … The recording seemed to concentrate more on the wild screaming of 18,700 kids than on the Beatles onstage.”

Watch the Beatles Perform 'Twist and Shout' at the Hollywood Bowl in 1964

Disappointed with what was captured, the live album was shelved ... until the Beatles returned for another two performances at the Hollywood Bowl in late August 1965. The band’s team recorded both shows and was once again disappointed with the results.

The next few years would be prolific, as the Beatles proceeded to change the course of popular music. The group released eight albums, four of which - Revolver (1966), Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), The White Album (1968) and Abbey Road (1969) - rank among the greatest in rock history. The band broke up in April 1970, with its last album, Let It Be, arriving a month later.

Seeing how Phil Spector had assembled the infamously difficult final LP, Capitol approached the producer and asked him to work his magic on the Hollywood Bowl tapes. Regardless of whether Spector thought the material unsalvageable, or the label was simply disappointed with what he turned in, nothing came of his work on the project.

Then, in 1977, Martin received a call from Bhaskar Menon, president of Capitol Records, asking him to listen to the tapes again.

“My immediate reaction was, as far as I could remember, the original tapes had a rotten sound. So I said to Bhaskar, ‘I don’t think you’ve got anything here at all,’” the producer later recalled. “But when I listened to the Hollywood Bowl tapes, I was amazed at the rawness and vitality of the Beatles’ singing. So I told Bhaskar that I’d see if I could bring the tapes into line with today’s recordings.”

Listen to 'The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl'

Martin recruited engineer Geoff Emerick and the two men began the arduous process of trying the salvage the best of what the tapes had to offer. The duo had 22 songs to work with across the multiple Hollywood Bowl shows. In the end, only 13 tracks would be deemed worthy of inclusion, as others were “obliterated by the screams.”

“The fact that they were the only live recordings of the Beatles in existence, if you discount inferior bootlegs, did not impress me,” Martin later admitted. “What did impress me, however, was the electric atmosphere and raw energy that came over.”

Even once he had a live album assembled, Martin was faced with another daunting task: convincing all four Beatles to give it their blessing.

“I rang John Lennon and told him about the recordings,” Martin recalled. “I told him that I had been very skeptical at first but now I was very enthusiastic because I thought the album would be a piece of history which should be preserved. I said to John, ‘I want you to hear it after I’ve gone. You can be as rude as you like, but if you don’t like it, give me a yell.’ I spoke to him the following day and he was delighted with it. The reaction of George [Harrison] and Ringo [Starr] was much cooler.”

Harrison believed the recordings were “only important historically, but as a record, it’s not very good.” Paul McCartney was simply “not that bothered” to give the project his time.

Despite a mix of reluctance and indifference, The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl was released on May 4, 1977. It hit No. 1 in the U.K. and reached No. 2 in the U.S., selling more than 2 million copies worldwide.

In the album’s liner notes, Martin wrote an explanation of why the project meant so much to him, describing the Hollywood Bowl shows as “a piece of history that will not occur again.”

“Those of us who were lucky enough to be present at a live Beatle concert – be it in Liverpool, London, New York, Washington, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Sydney or wherever – will know how amazing, how unique those performances were,” the producer explained.

“It was not just the voice of the Beatles; it was expression of the young people of the world. And for the others who wondered what on Earth all the fuss was about, this album may give a little clue. It may be a poor substitute for the reality of those times, but it is now all there is.”

In 2016, Martin’s son, Giles, remastered the album using modern technology and some additional tapes from the performances that had been discovered.

The new and upgraded LP, Live at the Hollywood Bowl, was released to coincide with the Ron Howard documentary The Beatles: Eight Days a Week. “What we hear now is the raw energy of four lads playing together to a crowd that loved them,” Giles explained to Rock Cellar at the time of release. “This is the closest you can get to being at the Hollywood Bowl at the height of Beatlemania.”