40 Years Ago: Why a Forgotten Debut Album Didn’t Doom Eurythmics

Dave Stewart didn't approach Eurythmics' all-but-forgotten debut as a pop album but more of a sonic experience. There were key figures beyond longtime collaborator Annie Lennox who helped shepherd this verite experience along, including Holger Czukay and Jaki Liebezeit of the German experimental-rock group Can, Kraftwerk producer Conny Plank and Blondie drummer Clem Burke. But Stewart had always been interested in found-object recordings.

"Since I was a child, I was obsessed not just with music but with recorded sound," he told Riff in 2020. "I would just record people in the street when I was 10 or 11. … Next door to the house where I grew up, there was a baker shop selling pies and bread, and I liked going in there and just sort of recording the sounds. Then I'd take them back to my bedroom and play them back."

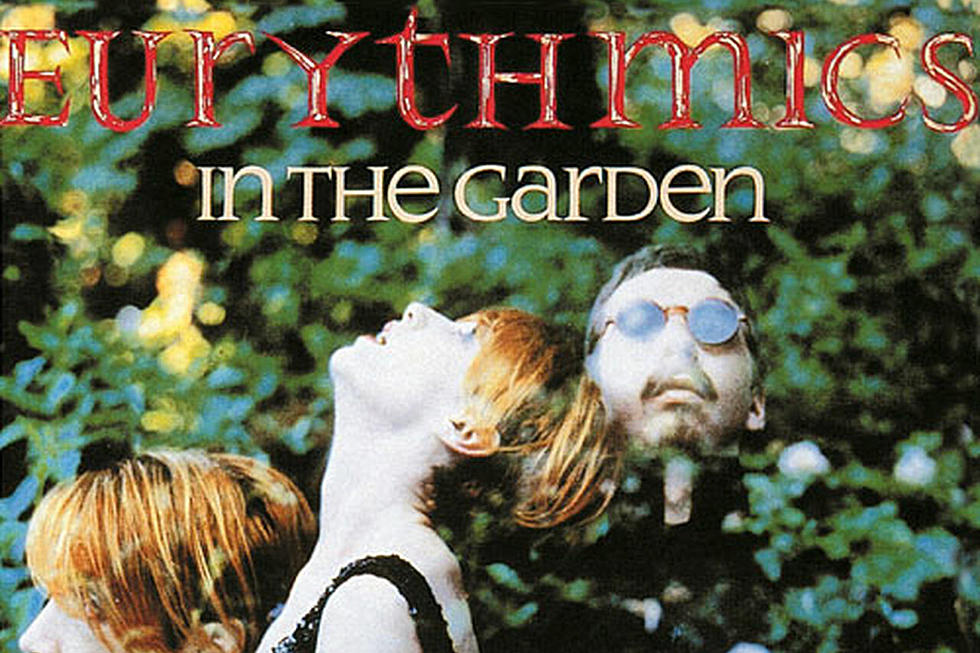

Same with In the Garden, which arrived on Oct. 16, 1981, featuring atmospheric playground noises in the opening "English Summer" and weirdly disembodied voices in "All the Young People." Hints of what would become a tighter, more pop-focused Eurythmics approach can be found during "Belinda" and "Revenge," but this first studio project is really better understood through moments like "She's Invisible Now," when they add a typewriter to create an icy counterpoint. Even "Revenge" is laced with a woman's laughs of satisfaction.

"On In the Garden, Conny Plank and Holger Czukay from Can and Jaki would teach me … to just record all different kind of sounds and mix them into the actual track — and even if you can't identify them, the whole track comes alive," Stewart told Riff. "I've always done that ever since, and it all goes back to being a kid and making a recording in the baking shop."

Maybe it was a bit too weird. Record buyers stayed away in droves, as In the Garden failed to chart anywhere. RCA tried floating a pair of singles, but "Never Gonna Cry Again" stalled at No. 63. "Belinda" sank without a trace. It wasn't exactly an auspicious beginning for Eurythmics, but Lennox and Stewart were battle hardened after having already overcome so much.

Listen to Eurythmics' 'Belinda'

They met in a health-food shop, becoming romantically involved as Stewart's nascent music career seemed to be making a fast start. Longdancer, his early band, had been signed to Elton John's boutique imprint when Stewart was just 18. Despite the marquee sponsor, however, Rocket Records was a mess, and Longdancer ended up going nowhere.

Then Stewart learned something new about Lennox: "When I first went to her tiny [studio apartment], she sang a song she'd written on a harmonium," Stewart told The Guardian in 2016. "It was like, 'Holy shit. What are you doing as a waitress? You're an artist.'"

They formed an early group called the Tourists, which again saw great potential lost to bad luck. The group released a trio of well-received albums, opened for Roxy Music on their Manifesto tour in 1979 and even scored a pair of Top 10 U.K. singles with a 1979 cover of Dusty Springfield's "I Only Want to Be with You" and 1980's "So Good to Be Back Home Again." But that was before Wagga Wagga.

"You see, we were coming to Australia on tour and we had a stop off in Bangkok, and there was a strike in Sydney and we couldn't land," Lennon told The Sydney Morning Herald in 2009. "So, they had to take all the passengers off and house them in hotels for a few days until the strike was over. It was an odd place to be stuck, wonderful in a way but extreme if you had never been there before."

Unfortunately, principal Tourists songwriter Pete Coombs came unglued while they waited in Wagga Wagga, located between Sydney and Melbourne. Already addicted to heroin, Coombs descended into a drink-fueled binge that ended with his split with the group.

"It was so sad," Lennox told the Morning Herald. "I don't know what his demons were, but they were very obvious. He was so gifted, but there we were, this remnant ragtag left."

Listen to Eurythmics' 'English Summer'

Adrift again, Lennox and Stewart turned their attentions to a small synthesizer – then picked a name based on Emile Jaques-Dalcroze's system of interpreting rhythms through the body. "I had decided to put the guitar down and try something I didn't know how to play," Stewart told Classic Pop in 2019. "Keyboards were completely alien to me, and I thought something new would come out through that."

There were more setbacks. Stewart's relationship with Lennox fell apart, too, though the duo somehow kept their creative partnership intact. An embryonic sound was emerging, then In the Garden bombed.

Stewart, however, remained undaunted. He set out to visit a local banker, "dressed up like a businessman – I had a briefcase and everything," Stewart said in Can't Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop's Blockbuster Year. "I told him that Annie and I were going to do something absolutely amazing and that the bank should invest in us."

Stewart's rationale was straightforward and very prescient: "I made the point that most bands spent 30,000 pounds just recording one album," Stewart remembered in Can't Slow Down, "but that we could buy the equipment we needed for 7,000 and then make all the albums we wanted."

They loaned Stewart the money, and that's just what Eurythmics did. By early 1983, Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) would become the first in string of Top 10 U.K. smashes. The conquest of the U.S., via the chart-topping title-track single, came next. They'd finally put it all together.

“On In The Garden, we'd been to Germany to record with Conny Plank, and we'd come across something which was underground, electronic, odd – and that'd left a really big impression on us," Stewart told Classic Pop. "So, when we came back to England, we had this sound that very much had its roots in Germany, and we added that to our English pop sensibility. That was how we came up with the Sweet Dreams ethos – cold, European, hard, tough-sounding synthesizers with a soulful voice."

Top 100 '80s Rock Albums

More From 92.9 The Lake